Not every kura can be a rustic reminder of the past. As technology advanced it became more efficient to house a brewery in a modern building that eschews traditional architecture. Surely the romantics among us love that old wooden kura with its elegant, aged beams and signature chimney. But let’s be honest–when it comes down to it, what really counts is the beauty of the product. That is something at which Ishimoto Shuzô, makers of Koshi no Kanbai, absolutely excel.

From the entrance to the company grounds, through the garden and on to the modern brewing facilities, what stands out is the immaculate appearance and attention to orderliness. The entrance is lined with a bamboo thatched fence that is replaced every year with help from a group of local craftsmen. No sign indicates what lies on the other side of that barrier. The reason given for the absence of a signboard is that Ishimoto Shuzô “doesn’t want to stand out too much but instead create harmony with the community.” The garden beyond is meticulously groomed, tended to by not one, but two loving gardeners. Leaves have been swept away and every shrub is properly trimmed and skillfully sculpted. The more than 100-year-old Machilus thunbergii tree that stands majestically in front of the facility’s entrance as if to welcome guests pre-dates the company’s existence.

Walking through the expansive facilities, I notice everything has been diligently arranged and stacked in order. A photo taken today of tools hung on a wall compared to one taken a month later would likely look exactly the same. After the rice steamer is cleaned, one would be hard-pressed to find a stray grain of rice on the floor underneath. Without having met the people in charge, one might imagine stern, unyielding generals barking out orders at the workers. But that would be far from the reality.

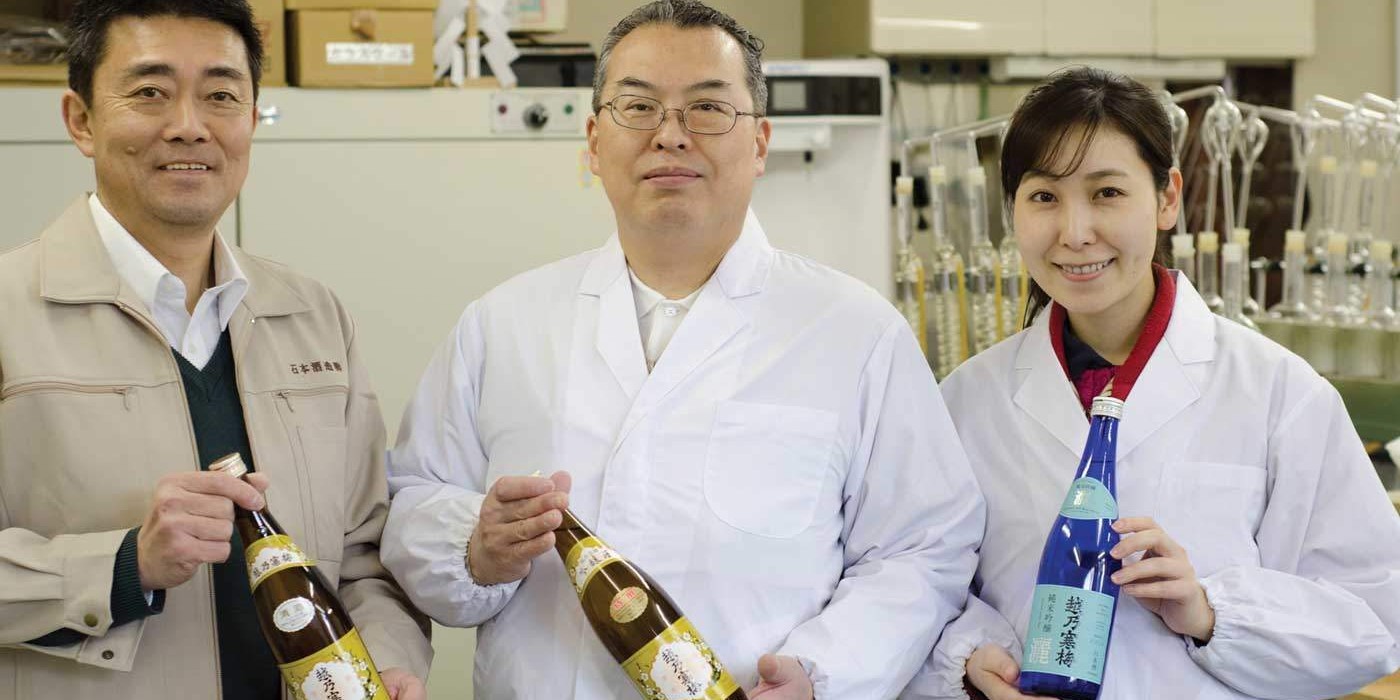

The captain of this ship, ebullient President Tatsunori Ishimoto, and his energetic commander, head brewer Shinichi Takeuchi, are light-hearted and approachable. As I walk through the brewery with them, they exchange genuine pleasantries with employees who are encouraged to spare a few playful moments for a photo op or chat with us. The image of a whip-cracking boss driving the troops quickly fades.

Ishimoto, a rather young president in his 40s, never really thought about running the company when he was growing up, but as the oldest brother he was preordained to become the head of the company started by his great grandfather Ryûzô in 1907. Ishimoto candidly tells us he wasn’t a serious student at his university, spending more of his time fooling around than studying, eventually leaving without finishing his degree. He went to work at Mihoh Shurui, a maker of liqueurs and alcohol (ethanol) that had a relationship with his father’s sake company. After a year and a half of learning about blending alcohol and producing liqueur and mirin, he returned to the family business, initially assigned to making deliveries.

After years of learning the business from his father, he finally took over as head of the company. Now ten years into his role as president, Ishimoto has embraced his position. He is quick to deflect praise for the company’s success, directing it instead to his staff for their diligence and commitment. Surely he is being humble, but in the sake industry, one cannot undervalue the importance of an adept brew team.

In head brewer Takeuchi, Ishimoto has the support of an individual in his 30th year at the company and 15th as toji. You will not meet someone more passionate about the product of his work. Taking us through the brewery, he can’t hide his excitement in describing how things work and what is happening at each stage, like a child thrilled to show his friends the new toys he got for his birthday. In the tasting room, he is clearly proud of the sake his team has produced and with good reason; it’s exemplary. He goes on to animatedly describe each sake in such depth and precision that you can almost imagine the taste prior to your first sip.

Takeuchi tells us, “Maybe it seems crazy, but I drink Koshi no Kanbai every day, not just for quality checks, but for enjoyment as well.” No one is more likely to notice slight variations than he is. He says he goes to work everyday thankful that he was given the opportunity to do this job. Admittedly not suited for a career in a suit and tie, he instead loves the simple pleasure of diving into the work with the other employees.

Last year Ishimoto Shuzô welcomed another veteran sake mind, Kenichi Watanabe, who retired after 25 years at the Niigata Prefectural Institute of Brewing and nearly a decade prior to that in the National Tax Agency’s sake division. He couldn’t stay away from the call of the industry for long and now serves in an advisory role at the company. Having worked at the Institute of Brewing, he spent years working toward elevating Niigata’s sake to the top rank in the country. He is a bit of a walking history book on Niigata sake and gives us a little insight into the evolution of the tanreikarakuchi style (crisp, light, and dry) for which Niigata is known.

As Watanabe explains it, in the 1960s, sake was mostly sweet, but there arose a demand for something drier and different in the Tokyo market. The pairing of the type of water in Niigata and the prefecture’s original rice, Gohyakumangoku, lent itself to the tanreikarakuchi style. The brewers and researchers at the time felt maybe that was the way to go. Also, as meat became more prevalent in the local diet, drier sake was sought after as a better complement. Those two things had a major influence on the trend and Niigata rolled with it. Toji Takeuchi is quick to add that high-end sake rice that has been well-polished is absolutely essential to produce the crisp, dry ginjo style for which Niigata is famous.

While the style is different than Koshi no Kanbai’s sake from a century ago, that basic precept of using adequately polished, quality sake rice was there from day one. The brewery was so adamant about this that after the second World War, when sake production was severely curtailed as the government strictly regulated grain usage and milling rates, Ishimoto’s grandfather, Seigo, rebelliously skirted the law. His clandestine efforts to ensure the company maintained a high level of quality make for a light-hearted tale now, but one has to imagine that in the post-war climate, he was taking some big risks. Much to the sake consumer’s benefit, Ishimoto’s father, Ryûichi, continued the company’s uncompromising stance when he took over. That tradition lives on in the present day.

The company’s name derives from an alternate reading of one of the characters for Echigo (the former name of Niigata Prefecture), read as Koshi, and kanbai, a plum tree that blossoms in the winter. The area near the brewery was known for its kanbai trees before rice paddies took over vast tracts of available flat land. A frequent subject of art and poetry with its delicate flowers blooming in the cold of January and February on snow-laden branches, the tree is a symbol of both beauty and perseverance. It also seems a fitting symbol for Koshi no Kanbai’s sake–elegant and resolute. Each winter as those plum trees are getting ready to bloom, so too does the next beautiful sake at Ishimoto Shuzô.